Hi all, and welcome back to rumblewrites. A few weeks ago, I wrote an article explaining what a digital archivist is and what one does. This time, I want to talk you through what it takes to become one. I’ll be focusing on my career path in the UK, but I’ll also provide some advice on how to break into the heritage sector more generally.

If you enjoy hearing about this side of my life, subscribe so I know you’re interested! And feel free to leave any questions down below:

Being a woman in STEM (kinda?)

Digital archiving is a difficult job to classify. It straddles the border between humanities and STEM: I work with digital objects, but for the purpose of historical preservation. I don’t know how to code or exactly how a computer works, but I do have a specific set of technical skills in quite a niche computational area. I’d say it counts as T: Technology, as it applies to the humanities.

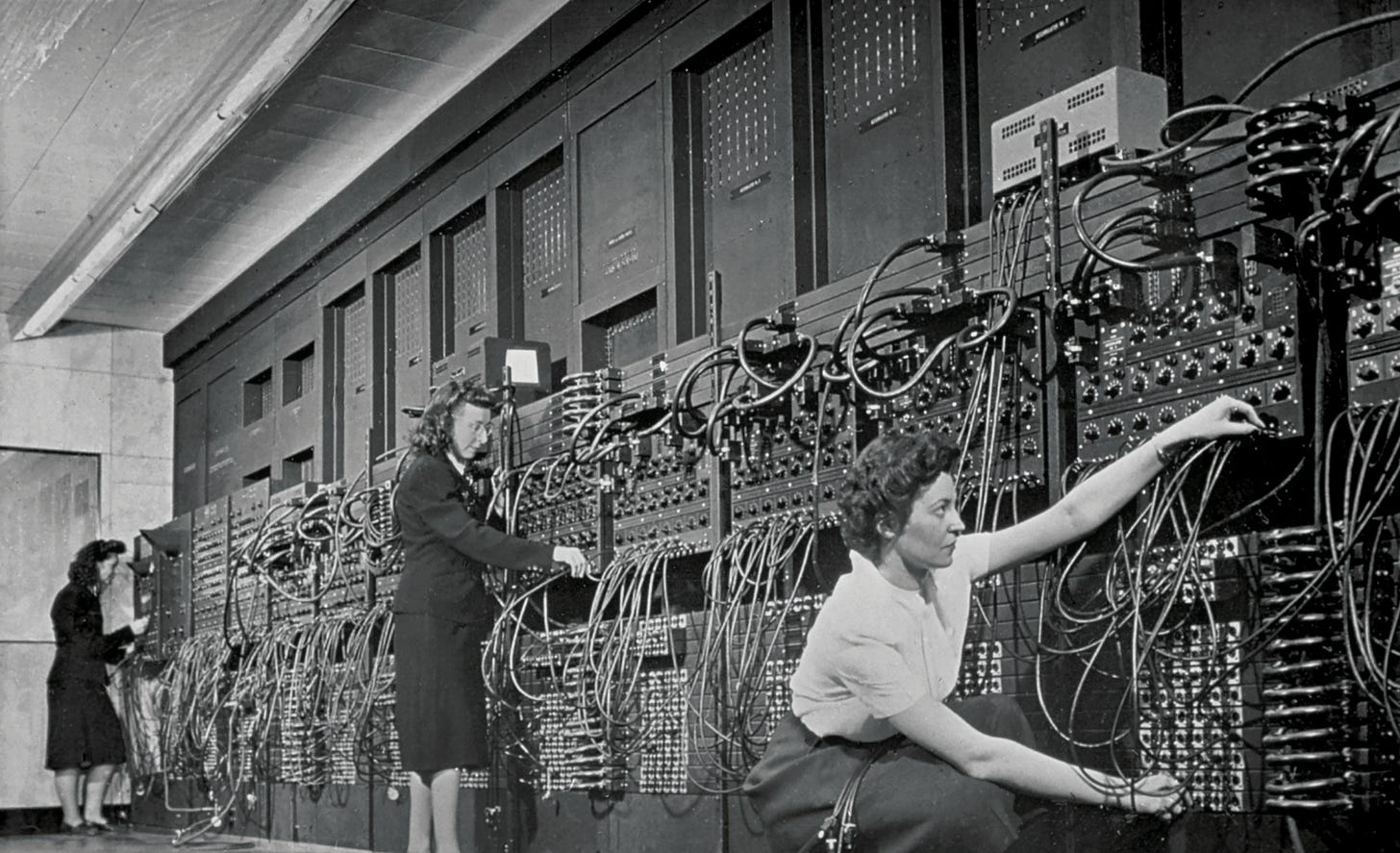

But regardless of just how STEM it is, I think we can agree it is a subcategory of computer science. The field I trained in used to be called Humanities Computing, in fact. And it’s comforting to know that there has been a long history of women working in this area. Ada Lovelace is generally considered to be the first computer programmer and, following her, the task of programming was often given to women. Mostly because it was seen as menial and unskilled, compared to the hard, physical job of building a computer (which, of course, was set aside for men).

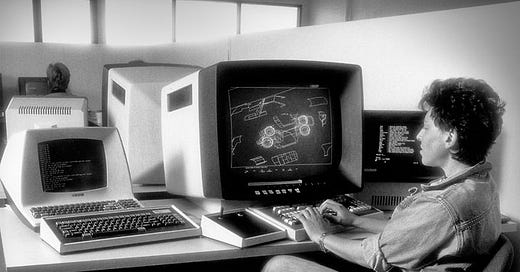

Computer operators with an Eniac - the world’s first programmable general-purpose computer

However, by the end of the 1960s, this dynamic was starting to shift. More weight was being given to the skill needed for, and general importance of, computer programming. And so men started to enter this side of the workforce. While women still made up just under 50% of workers, few were promoted to positions of power. The field of computing quickly became male-led and male-dominated, and that’s where it’s stayed. According to a 2024 study, only 19% of the global software engineering workforce is female. This needs to change.

I’ve included this little introduction to prove that the digital space is one were women are needed, and where they belong. Not only that, but it’s possible to still work in a humanities field and use technology in your day-to-day work. You don’t have to be a computer scientist or engineer to be the technical person on your team, and I’m proof of that.

Now, onto your questions:

My path

Q: How did you get into doing this work? Was it something you always wanted to do or was it like a happy accident you fell into? [by

]

Definitely a happy accident. I feel like my whole academic / professional life has been one big happy accident, in all honesty. I’ve never had any specific career goals, and when I was younger my aspirations ranged from a forensic scientist to a translator, writer, and lawyer. And when it came time to pick my A Levels, I just chose the subjects I was interested in: English Literature, History, French, and Latin.

I always thought I’d study English at university - it was my favourite subject, and I just loved to write - but a combination of rubbish texts and a not-so-encouraging teacher made me change tact. I instead chose to study a joint honours programme in Classics and History at Durham. It was during my (covid-riddled) second year that I attended an online event hosted by the York Festival of Ideas on ‘The Future of the Past: Digitalised Manuscripts’. The talk outlined the Polonsky Foundation’s work to digitise historical texts and make them available to a broad global audience. The idea of using technology to democratise history was something that really spoke to me, and I ended up researching the field of ‘digital humanities’ more earnestly.

The following year, I had secured a place at UCL to study Digital Humanities and was about to undertake a work placement at a London-based research hub to digitise 3D objects in a process known as photogrammetry.

During my master’s degree, I was exposed to a wide range of digital humanities ideas and techniques, including programming, web design, digital accessibility, data cleaning, natural language processing, and AI. Of particular interest was a module on Medieval Manuscripts, where I learnt more about the processes of digitisation and web hosting. This confirmed my desire to pursue a career in digital history.

My first job was as the Digitisation Assistant for a corporate archive. I was responsible for scanning and editing archival material, as well as basic cataloguing and social media assistance. However, I didn’t feel myself progressing, and so after a year and a half in this role, I decided to start looking elsewhere. That’s when I landed by current role: as the Digital Archivist for a local council. And let me tell you, I am much happier here. I have responsibility over the whole digital archive, and I feel like I’m making a real, positive difference.

Advice for others

Q: Do you have any advice for someone who is interested in getting into this field of work? [by

]My first piece of advice is just: go for it. A lot of people deterred from a career in the arts because they’ve been told the pay isn’t good, the field has no future, it’s too specialised, etc. And while those things may be true to some degree, so what? It’s a nightmare to break into any field, people are constantly being laid off, and you know what will make it even harder? If you’re not actually passionate about the work you’re applying to do.

Creative fields are suffering at the moment, that’s no secret, but they’ll suffer even more without people working in, and advocating for, them. Archive work is a labour of love: the people are here because they love it, and because they care. They want to be the custodians of our collective past because they believe in its importance. And they’re willing to tackle the hurdles as they come. If that sounds like you, keep reading.

Now, some more practical advice: get experience, and get qualified. Collections care, be that museum, archive, library, or digital, are specialised fields. In the UK, you’ll need at least an undergraduate degree in a humanities subject to get your foot in the door, but more often than not, you’ll also need an accredited postgraduate qualification in your area of interest (e.g. for archives, UCL’s Archives and Records Management MA course).

In addition to this, you’ll need some hands-on experience working with collections. While experience is helpful in any field, it’s become a quasi-requirement for collections work. Luckily, archives and other institutions are always looking for volunteers! Just search around in your local area and I’m sure you’ll find something. I’d recommend doing this a little earlier than I did (i.e. around sixth form / 1st year of university time), just to give yourself some leeway to change paths if you discover it’s not something you enjoy. I will say the reality of archives work is a little different to the mysticism surrounding “archives” in the popular imagination…

It’s unfortunate that these requirements often present a barrier to entry for many potentially great archivists and librarians. It’s hard to give up time for unpaid work (paid work does exist, but it’s very rare and often goes to volunteers who already have some experience), and many just can’t afford to get a second (or even first) degree. I’d change things if I could, but this is the reality of the sector as it stands.

But if you still want to, and still can, do this: go for it. Just remember that what I’ve outlined here are the basic requirements of the job. They’ll help you get a foot in the door, but they won’t make you stand out. That’s something you’ll have to figure out on your own.

Argh, fascinating! And hello from a fellow Durham alumni – graduated BA Ancient History in 2019

I came from an Information Sciences background, majoring in Records Management and Archival Management, but sadly, the job is so limited in my country, hence, transitioning into a Talent Development role instead. It makes me proud that there is somebody like you who continues the legacy of preserving the past for future generations. Keep up the good work, Lucy!