Archiving our (digital) past

Discussing my day job. What does a Digital Archivist do?

Hi all, and welcome back to rumblewrites. Today’s post is all about digital archiving, following a Note I posted last week:

I was so pleased to see such a positive response to this question! It’s very exciting to know that so many people are interested in what is quite a niche (but, I’d say, important!) job. So today I’ll just be providing a basic overview of what digital archiving entails, as well as answering a few of the questions I received from you guys. But I can’t cover everything in one post, so if you’re interested, I’d love to make this into a series! I’ve made a note of all the questions I’ve already received, but feel free to ask more. And please do like, comment, subscribe if you’d enjoy this post:

What is a Digital Archive?

A digital archive comprises of digitised and born-digital content. That is to say digital objects which have been created from an original analogue object, such as scanned images of books, and objects which originated digitally, like films and music.

What does a Digital Archivist do?

The vast majority of archives have significant backlogs of material they need to catalogue, digitise, and otherwise tackle. In the context of digital archiving, this is usually in the form of objects being held in improper (read: obsolete) storage. On these devices, digital objects are not safe.

It’s a common misconception among the public and archivists alike that digital objects require less attention than analogue materials. But this couldn’t be further from the truth. Digital objects are actually less stable, and less likely to be happy if left alone: while a book can sit untouched on a shelf for decades, passively storing digital objects for just a few years can be highly detrimental. Remember: today’s new technologies are tomorrow’s obsolete media.

A historic lack of understanding of, and therefore lack of care for, these digital objects means that they are often in a pretty critical state. And even when they’re not, it’s still important that we act now, before it’s too late. And that’s where I come in. It is my job to make sense of, rescue, manage, and preserve these digital objects. Both because of their historical value, and also to ensure they remain accessible for current and future audiences.

It’s interesting that many of the questions I received under my Note didn’t ask about this, but rather were focused on the act of digitisation. This actually isn’t what a Digital Archivist does (generally). In smaller institutions like my own, this is often the job of volunteers, or it can be done by any member of an archival team. My role purely revolves around the digital objects themselves, and carrying out the actions which are necessary to keep them safe and happy.

Now, let’s get onto some questions:

Where / how do you store your archive?

From:

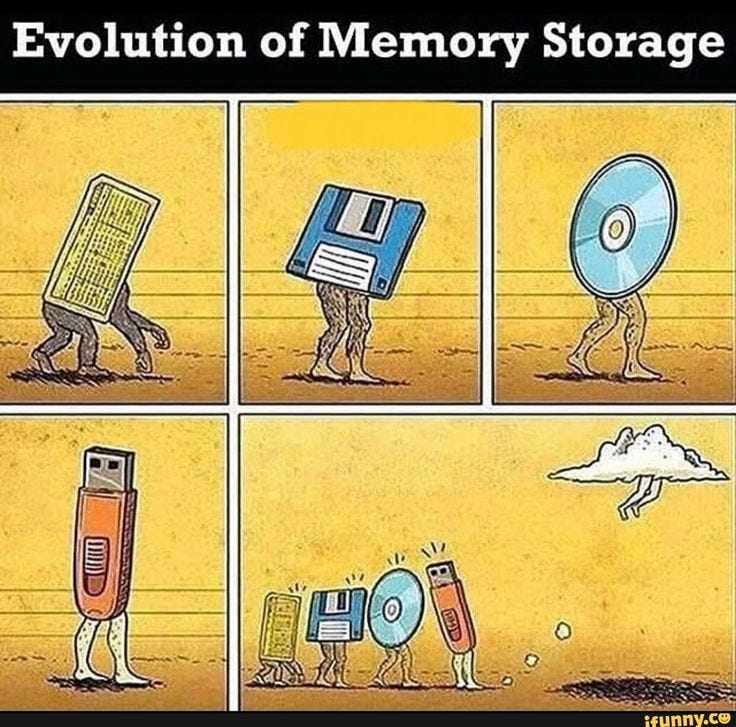

Our digital archive is held across a variety of modern and obsolete media, including cloud storage, CD-ROMs, film reels, hard drives, and cassette tapes. These latter items are held in a secure storage room underground.

Do you see digitising as more of a preservation tool, or is it more about wider access?

From:

Digitising is not preserving. Let’s consider that on two levels:

What is a digital surrogate? It’s a representation of a physical object in a digital format. Right. But what does that mean? It means that it is a snapshot of the visual components of an object at a single moment in its life. If I were to set the object on fire straight after taking the photo, it is no longer an accurate depiction of it. Of course, this is a rather extreme example, but change does happen. Also, a photo can only ever capture the visual elements of an object. It gives no sense of its size, weight, feel, smell, texture, etc. It is simply a surrogate: something that stands in the place of an original, but which is also separate from it, with its own unique (digital) properties.

Digitisation is, or at least can be, an invasive process. Without specialised equipment or a conservation department (which the vast majority of archives in the UK do not have), this means that digitisation may not be possible. And it may in fact be more preservation-friendly not to digitise the object.

So, digitisation is about widening access to the content contained within a physical object. And that’s no minor thing. In the UK, most archives don’t charge fees for viewing their material, but this doesn’t mean there aren’t any barriers to access. Location, physical ability, poor cataloguing, no web presence, or just the perceived social role of archives in a community are all limitations which restrict who can view certain objects. As a means of providing some insight into these objects, digitisation is therefore integral to widening access to, and fostering public interest in, historic collections.

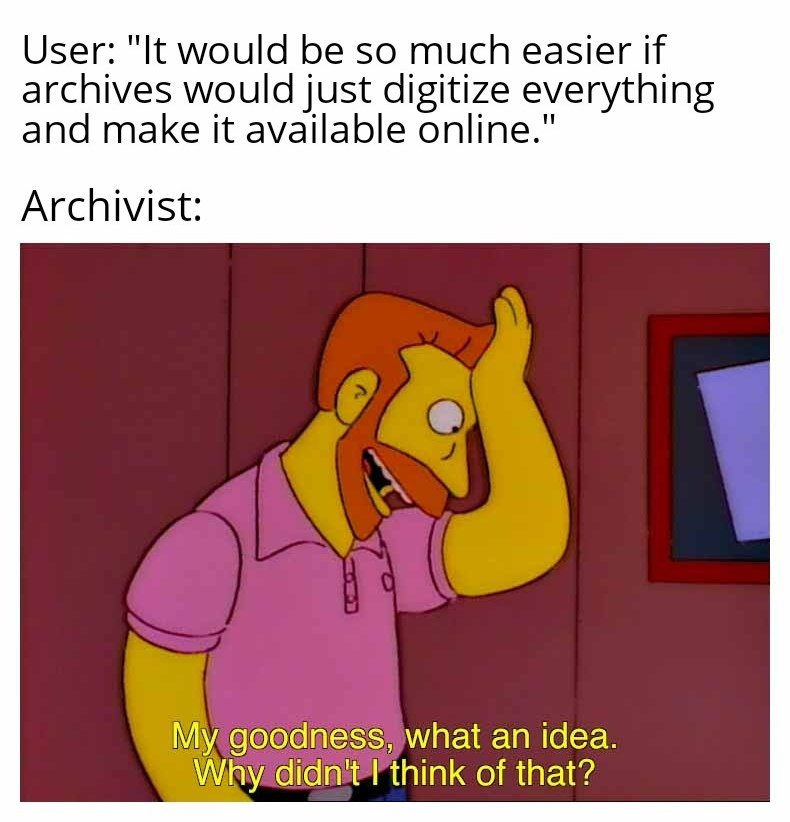

On a related note: why don’t we just digitise everything?

From: me

Err, many reasons:

Cataloguing backlog. If we haven’t figured out what an object is yet, what’s the point of putting it online?

Stability. Would scanning the object damage it? What costs would be incurred by getting it reviewed, and perhaps worked on, by a conservator?

Scale. The archive I work for is relatively small, but we still have tens, if not hundreds of thousands of physical objects.

Manpower. Who’s scanning all this?

Time. When?

Equipment. With what specialised equipment, that they’d need training to use?

Infrastructure. Do we have the systems and web presence capable of storing, preserving, and hosting these images?

Rights. Even if we did, can we ethically display these images publicly? Or would that violate copyright / GDPR laws?

And lastly: money. All this costs a lot, and money is something which the heritage sector famously does not have.

What efforts are being made in digital archiving practices to ensure the longevity of the preserved works?

From:

We’ve established that digitisation ≠ preservation. So what does it actually involve? Well, lots of things. But here’s a few:

LOCKSS: Lots Of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe. We create backups. At least 3, stored across different media and kept in different geographical locations. But it’s important to note that storage still ≠ preservation! Making copies and putting them somewhere is pretty much useless without active management of them.

Bitstream preservation. This is an example of active management. A bit is the basic unit of information in computing. It can have only one of two values commonly represented as either a 0 or 1. Every digital file is made up of a bitstream, or a sting of these 0s and 1s. If left alone, these 0s and 1s may change, randomly, and corrupt or otherwise damage the file. To ensure this doesn’t happen, we therefore need to capture and record the object’s original bitstream, and then repeat and check it at set intervals. If a deviation is found… well, that’s what backups are for! The original file can be restored using one of the backups.

Monitoring. Storage devices, software, file formats, you name it: all digital products have an expiry date. When something is no longer supported (or preferably before that point), we need to migrate it to a newer, better-supported system, type, or device.

Thank you for reading about my little niche of the world, and please do let me know if you’d like me to go into any of this in greater depth.

Thank you for this information and I’m excited to keep reading future posts in the series! I have recently been researching graduate programs for Library Science, Archives, and Media preservation - I was wondering if you have any advice for someone who is interested in getting into this field of work?

this was such a interesting read! can i ask how you got into doing this work? was it something you always wanted to do or was it like a happy accident you fell into?