Hi all, and welcome back to rumblewrites. When I sent this newsletter out last week, I only had 17 subscribers, and now I’m at 150! Here’s what I’m doing to celebrate:

Starting with this, 1-2 posts per month will be for subscribers only

I’m turning on paid subscriptions. These are set at £5/month, and I’m currently offering a 20% discount on annual pledges:

Upgrading to a paid subscription is, of course, voluntary. While it would help fund further content, I’m committed to publishing every week regardless.

Thank you for your support.

What are rare books?

I’m guessing most of you here are bibliophiles. Whether you love paperbacks or eBooks, reading poetry or epic fantasy, hopping on the latest trends or sticking to the classics, a lot of us value books. But there’s a difference between your standard book and a rare book. For starters, there are specialists who value and trade these items: like Peter Harrington and Shapero in England. But it’s generally agreed that for a book to be considered ‘rare’, it must stand out in at least one of the following areas:

Historical significance - provenance (especially if it’s well-documented), age, previous ownership, etc

Condition - general wear and tear, quality of binding, completeness, etc

Edition - especially first editions

Additional content - signatures, marginalia, special preface, etc

And when the stars align, books can become fortunes.

Why do I collect?

During my Master’s degree, I took a module on manuscripts and rare books. This primarily covered palaeography and codicology* of manuscripts from the 1st to 15th centuries, as well as transcription and book history. As part of this course, we were taken on a visit to the special collections at Eton College, and this was where I fell in love with rare books.

As soon as my course was drawing to an end, I started applying for jobs in the heritage sector. I was actually offered a position as an Antiquarian Bookseller, but I turned it down after one of the interviewers warned me that the business-side of selling could rid books of their joy. I instead accepted a different offer - my current job - where I work with rare books in an archival capacity. It was also at this point that I started building my own, personal collection (if you can call it that - I only have 4 books!).

While factors like scarcity and historical significance are definitely important to me, I do think there’s another area to consider:

Sentimental value

I choose books that are meaningful to me, regardless of their condition or proliferation. These usually fall within the following categories:

Literature or historically significant books from late 18th / early 19th century Britain / France

Anything related to poets I enjoy

Medieval manuscripts (although I have none of these yet)

please oh please let me find a mere scrap that doesn’t cost the world

Basing my purchasing choices on personal preference, as well as looking in non-specialist stores, has massively lowered the price of collecting for me.

*palaeography - the history of scripts; codicology - physical aspects of the book. When studied in combination, these can help us ascertain the provenance, dates and previous ownership of a manuscript / rare book.

Here are 2 of the books in my collection. Maybe this will give you an insight into me, but I hope at the very least it shows you that rare book collecting doesn’t have to cost the world.

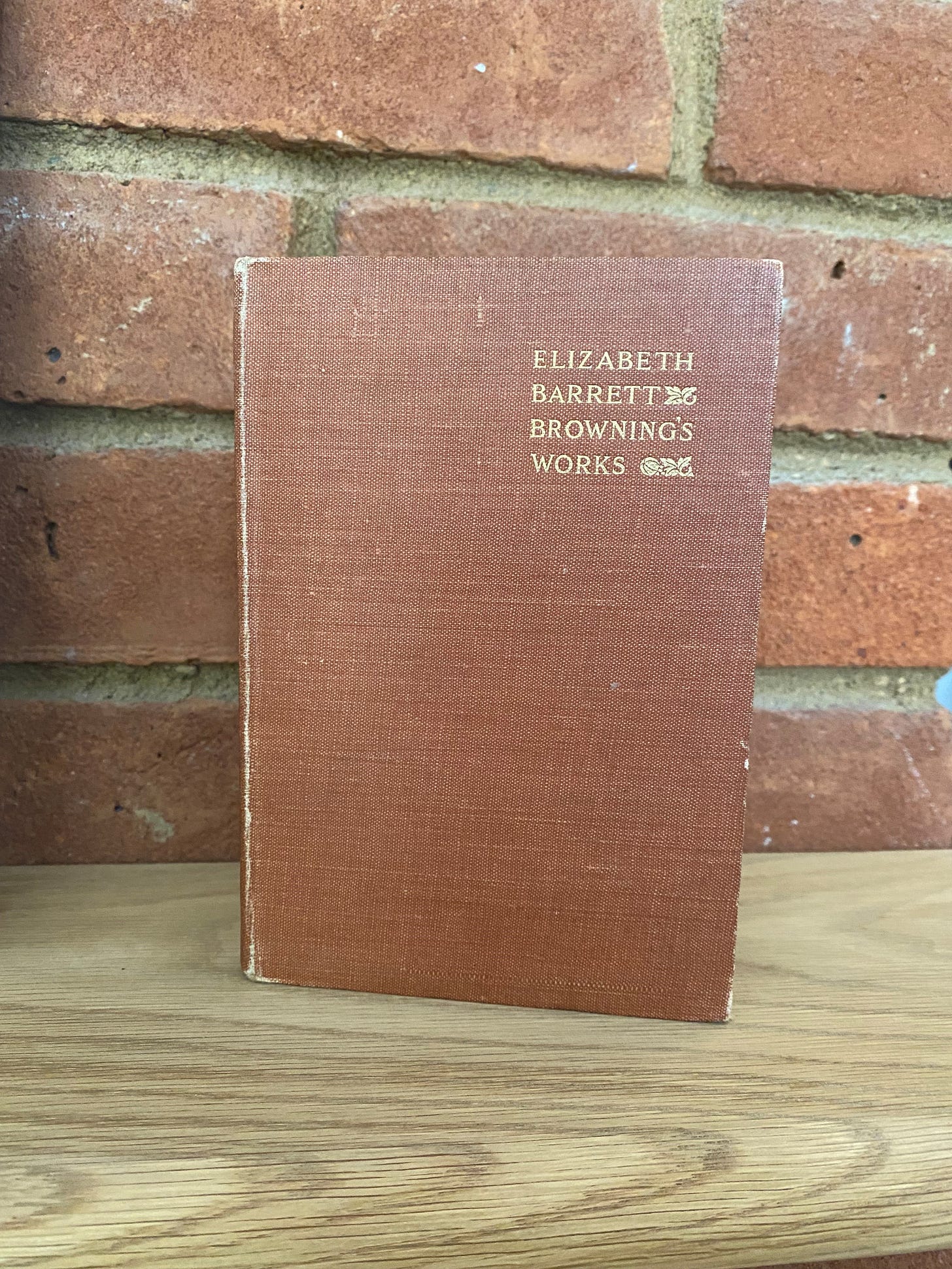

The Poetical Works of Elizabeth Barrett Browning vol 2

Published in 1907

This book is a re-issue of the original 6-volume edition, condensed into 3 pocket volumes. I have volume 2, which features poems, sonnets, sonnets from the Portuguese, Casa Guidi windows, poems before Congress, and last poems.

It was originally sold by Smith, Elder & Co, a (now defunct) British publishing company which achieved its first major success with the publication of ‘Jane Eyre’ by Charlotte Brontë (then Currer Bell). The company was purchased by one John Murray in the 1900s, and now resides as part of the Murray Collection in the National Library of Scotland.

I purchased this book almost a year ago now, for £4(!) at a second-hand bookshop in Swanage, Dorset.

It’s in great condition, and even includes this beautiful drawing of Elizabeth Barrett Browning, with a cover sheet to protect it:

I first encountered Elizabeth Barrett Browning at GCSE, when I studied her ‘Sonnet 29 – I think of thee’ as part of a through-the-ages course on love poetry. She was a Romantic, and many of her sonnets are thought to be written for her husband Robert Browning, another Victorian poet.

Since then, I have discovered her other works. While much of her writing is concerned with personal conflicts and emotions, I enjoy her most for her creative engagement with contemporary issues. In particular, her writing features references to women’s rights, child labour and imperialism. She used poetry as both a form of art, and a means of political expression. In reference to my article a couple of weeks ago about misogynist fantasy writers, this is a strong woman.

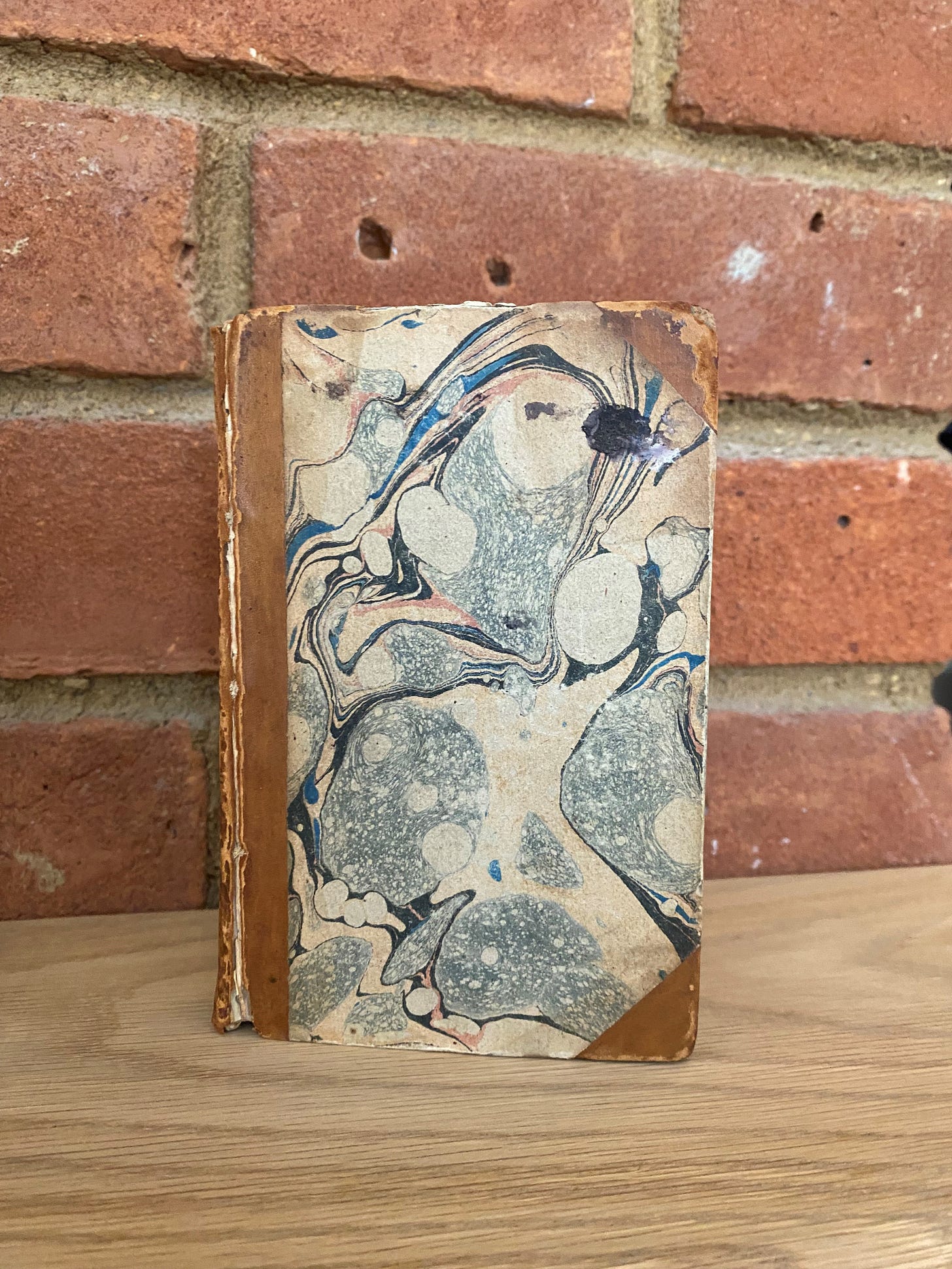

Code de Commerce

Published in 1808

Now this one is a little more exciting for me. As a massive French Revolution / Napoleon fan, when I came across this book, I just knew I had to buy it! It was my first rare book purchase, and although it’s torn and kind of yucky, I love it.

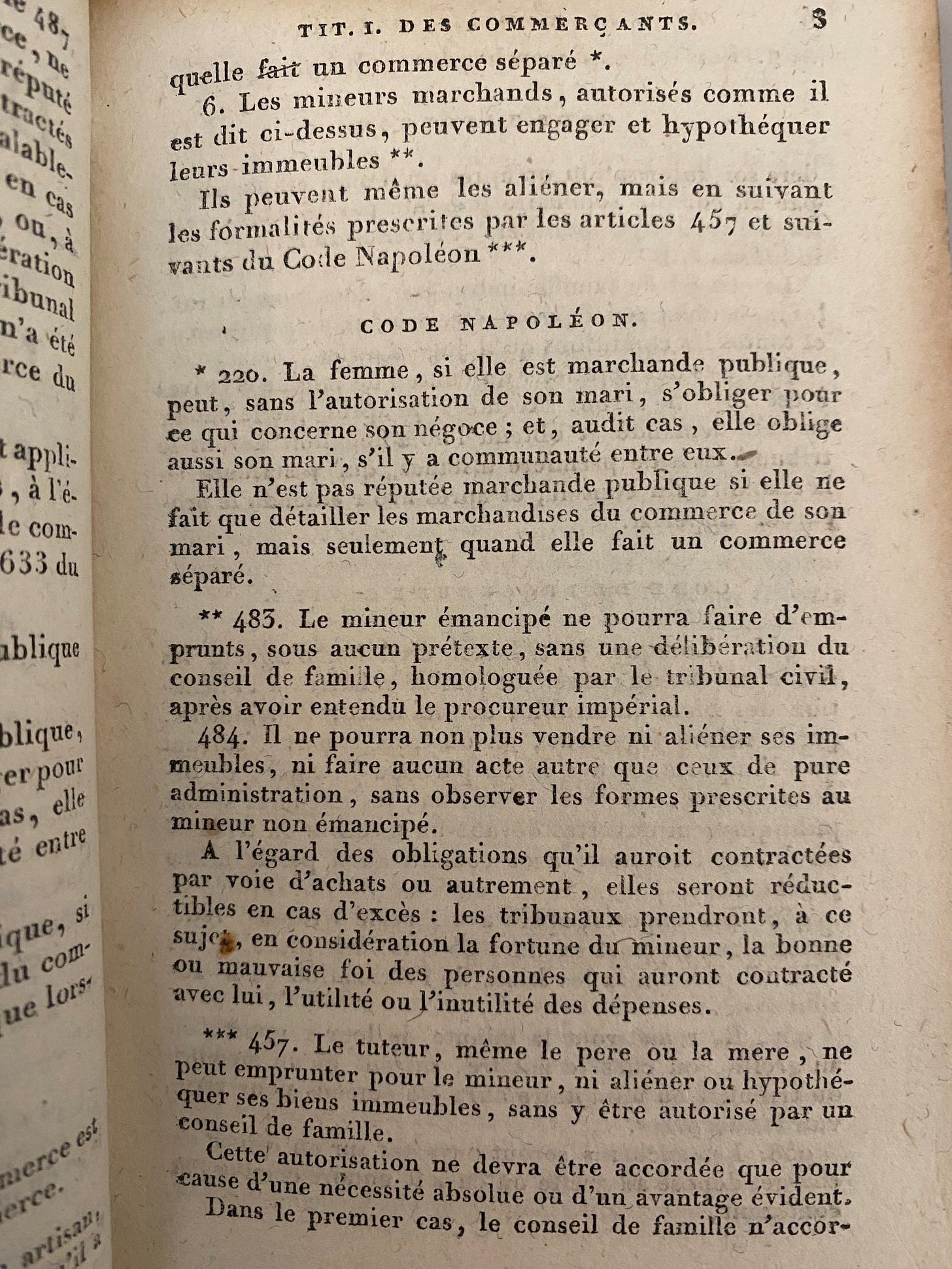

It was originally published in Paris by brothers Pierre (the Elder) and Firmin Didot. In the late 1700s, the brothers published works by some of the great writers of antiquity, including Horace and Virgil, and even roped Jacques Louis David into drawing some of the illustrations! Their publications boast a distinctly Neo-classical style, as well as Firmin’s famous creation: the Didot typeface (pictured in my copy here):

I purchased this book in the antiquarian section on the basement level of the Waterstones in Gower Street for, get this, only £45!

The Code de Commerce itself was part of Napoleon’s reorganisational plans initiated after his successful Coup of 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (9 Nov 1799). He wanted to rebuild the civil order of society after the Revolution, and mark it as distinct from that of the dreaded Ancien Régime:

« On a tout détruit, il s’agit de recréer. Il y a un gouvernement, des pouvoirs, mais tout le reste de la nation, qu’est-ce ? Des grains de sable. Nous sommes épars, sans système, sans réunion, sans contact. Tant que j’y serai, je réponds bien de la République, mais il faut prévoir l’avenir. Croyez-vous que la République soit définitivement acquise ? Vous vous tromperiez fort. Nous sommes maîtres de la faire, mais nous ne l’avons pas, et nous ne l’aurons pas, si nous ne jetons pas sur le sol de France quelques masses de granit. »

ref. Napoleon Bonaparte, (8th May 1802 / 18 floréal an X), in: Thibaudeau, ‘Mémoires sur le Consulat: 1799 à 1804’ (1827), pp.84-85

Other laws introduced as part of this Napoleonic reform were the Banque de France (1800), Code civil des Français (1804), and Code d'instruction criminelle (1808).

The Code de Commerce was drafted throughout 1807 and officially came into effect on 1st January 1808. It crowned the attempts made throughout the 18th century to update the 1673 Merchant Code, all of which had failed or been abandoned in favour of other, more pressing projects. It took the bankruptcies of 1806 for it to gain any real traction: Napoleon ordered the council to start work immediately, and over the course of 68 sessions held within a 9-month period, they fashioned this code. And now I own one of the original copies... there’s nothing cooler than that.